- Home

- About us

- News

- Events

- EXPORT Export

-

BUY

Buy

BuyBuyFood and beverage Beef Caviar Dairy Products Fruits Healthy foods Olive oil Processed Foods Rice Sweets, honey and jams Wines ICT Software development Technology products

- INVEST Invest

- COUNTRY BRAND Country Brand

-

INFORMATION CENTER

Information center

InformationCenterInformationCenterReports Country reports Department reports Foreign trade reports Product-Destination worksheet Sectors reports Work documentsStatistical information Classification Uruguay XXI Exports Imports Innovative National Effort Macroeconomic Monitor Tools Buyers Exporters Investors

- Contact

-

Languages

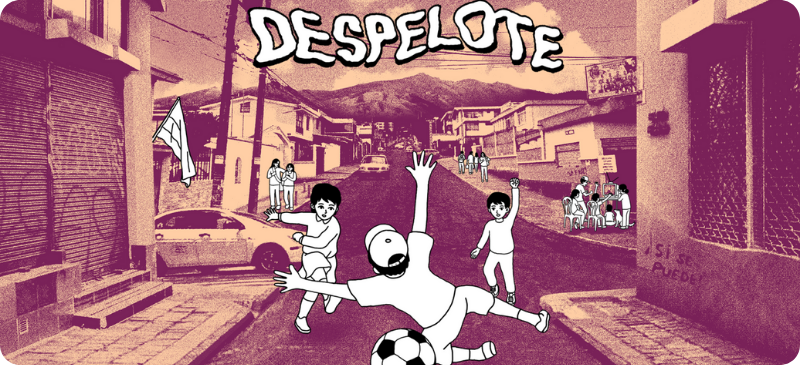

Local identity as a global advantage: lessons from Despelote for Uruguayan video games

Invited by Uruguay XXI to LEVEL UY 2025, Ecuadorian game creator Julián Cordero shared how a project deeply rooted in memory, neighborhood life, and soccer managed to break into leading international circuits

Share:

“Despelote is a game about soccer and people,” Cordero says. He is talking about his video game, but he could just as easily be describing everyday life in many Latin American countries where “la pelota” — the ball — shapes social rhythms. Born in Quito and now based in New York, Cordero visited Uruguay at a pivotal moment in his career: Despelote had recently been selected and nominated at festivals such as Tribeca and the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, won the Best Audio award and several nominations at the Independent Games Festival (IGF) at the Game Developers Conference (GDC), and earned a nomination at The Game Awards, the video game industry’s equivalent of the Oscars.

His participation in LEVEL UY 2025, within the Uruguay XXI agenda, aimed to showcase his creative process and offer an inspiring example of how a strongly local video game can reach global audiences — and help position a country internationally.

Cordero describes Despelote as “a semi-autobiographical everyday adventure set in Quito in 2001.” The player controls an eight-year-old boy — “an idealized version of myself, a little Julián obsessed with soccer, while Ecuador was closer than ever to qualifying for the World Cup for the first time,” he recalls. That tension between intimate life and a historic national moment runs throughout the game.

The result is a title that, from a single neighborhood in Quito and a deeply personal memory, became part of the global conversation about video games. How can something so local achieve that reach? For Cordero, the key is embracing what is unique.

The “universality of the specific”

One of the ideas he emphasized most in Montevideo was the value of local identity as a competitive advantage abroad. “I feel the game became a kind of collective memory of that moment, of that year, 2001. The memories are very specific, but somehow collective,” he explains.

That specificity — the neighborhood, the park, the voices, the Ecuadorian national team’s World Cup journey — did not hinder internationalization. On the contrary, it became an asset. “There’s a universality within the specific. The more specific we were, the more people connected with it. I don’t know why it works that way,” he admits.

For Uruguayan studios, the message is clear: exporting video games does not require abandoning what is local. Montevideo, the countryside, the coast, soccer culture, music, humor, and everyday rhythms can, as in Despelote, become powerful ingredients for building products that stand out in markets saturated with generic worlds — while also strengthening the country’s global presence.

Culture as an exportable language

Despelote has no pristine stadiums or blockbuster scenes. Instead, it features a park inspired by Quito’s La Carolina, and a ball traveling through that everyday landscape.

Soccer is as central to Ecuadorian culture as it is to Uruguayan culture. But Despelote approaches it differently from traditional sports simulators. This combination — a strong cultural code treated through ordinary life rather than spectacle — offers a clue for Uruguay: using regionally shared symbols, but seen from the sidewalk, the playground, and casual conversations, can lead to products with major export potential without losing local roots.

Working with real voices, accents, and speech patterns gives the game credibility and builds shared memory. In export terms, it shows that language, accent, and local references are not obstacles but differentiators. Keeping Spanish, regional expressions, and cultural nuances can become a recognizable hallmark for global audiences seeking authentic experiences.

Publishers, demos, and financing: the strategy behind the case

Seven years of work lie behind Despelote. Early on, the project received support from the Ecuadorian Ministry of Culture through a dedicated video game fund.

When seeking international financing, the team began with a clear intention: they wanted to create an unmistakably Ecuadorian game, very specific in its relationship to soccer and the city — and they needed partners willing to embrace that vision.

Cordero avoids offering simple formulas, but Despelote’s journey leaves concrete lessons for studios presenting local projects on global stages.

One lesson is the importance of market timing. When they sought funding, several international companies were opening programs for diverse and original projects. “We were lucky with the timing,” he says. Today, he sees a more challenging landscape, even for strong proposals.

Another key element was the playable demo. During the pandemic, the team produced a polished pitch and demo and sent them to a very short list of publishers they had researched in advance. Of the three ideal options, two expressed interest. The final choice was Panic, publisher of Firewatch and Untitled Goose Game.

“The conversation with Panic gave us confidence: it was clear they had played the demo, discussed it, and understood it. They didn’t ask us to make the game more ‘traditional’; they wanted to support that specific vision,” he recalls. For him, the demo outweighs any slide deck: “If the demo is strong, the pitch deck can be simple. In the end, publishers will handle the selling — they just need to see the game in action.”

While Despelote was not designed to maximize sales, Cordero believes the game has strategic value for its publisher: building a recognizable catalog associated with distinctive, risk-taking experiences.

Global niches for original stories

In Montevideo, Cordero also compared the Ecuadorian and Uruguayan game industries. Ecuador, he notes, still lacks a global success story like Uruguay’s Kingdom Rush, and has fewer long-established studios. Uruguay, in his view, already has a more mature ecosystem with experienced developers — an advantage not common in Ecuador.

For Uruguay, his case offers a double lesson: highly localized projects can indeed achieve international visibility, and a mature industry may be even better positioned to capitalize on this approach.

The conversation also touched on a familiar tension: should a studio make “the game it wants to play,” or the game the market wants? Cordero acknowledges the value of reading trends, but his path was different.

“I was in artist mode. I wanted to explore what soccer meant in my life and in my country’s life. If I hadn’t truly believed in that idea, the game wouldn’t be what it is,” he says. Instead of chasing existing formulas, he trusted that outside the mainstream there are global niches eager for very specific stories — if they are well crafted and meet the right partners.

Despelote shows that a game born from a deeply personal experience, built with accessible resources, documenting a real city, and preserving its language and accent, can reach global audiences when identity, narrative depth, and internationalization strategy align.

For Uruguay — already home to established studios and international successes — Cordero’s example reinforces a strategic message: video games can also be powerful vehicles for country branding and creative-content export, as long as studios dare to tell their own stories, from here to the world.