- Home

- About us

- News

- Events

- EXPORT Export

-

BUY

Buy

BuyBuyFood and beverage Beef Caviar Dairy Products Fruits Healthy foods Olive oil Processed Foods Rice Sweets, honey and jams Wines ICT Software development Technology products

- INVEST Invest

- COUNTRY BRAND Country Brand

-

INFORMATION CENTER

Information center

InformationCenterInformationCenterReports Country reports Department reports Foreign trade reports Product-Destination worksheet Sectors reports Work documentsStatistical information Classification Uruguay XXI Exports Imports Innovative National Effort Macroeconomic Monitor Tools Buyers Exporters Investors

- Contact

-

Languages

A Journey Through Uruguayan Literature: Publishers Who Read Montevideo Like a Book

Uruguay XXI organized a literary mission that blended meetings with the publishing sector and a heritage tour of the places where the country’s literature was forged.

Share:

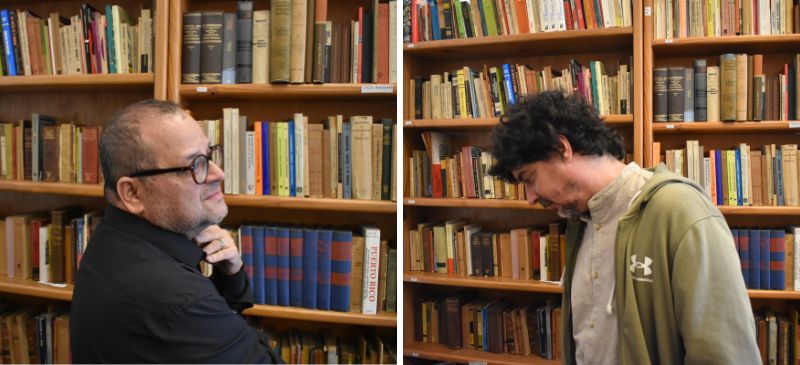

Montevideo unfolded like a book meant to be read on foot. Between September 24 and 26, Uruguay XXI invited two publishers—Santiago Tobón of Sexto Piso (Mexico–Spain) and Sandro Aloisio of Grupo Escala (Brazil)—to discover those pages through a program that combined meetings with publishers, authors, and illustrators, and visits to the houses, cafés, and institutions that have sustained Uruguay’s literary tradition for more than a century.

“We wanted them to experience not only today’s publishers, authors, and illustrators, but also the living history behind them—the places where our literature was shaped,” explained Omaira Rodríguez, Creative Industries Promotion Specialist at Uruguay XXI, who guided the visitors throughout the tour.

From the National Academy of Letters to Café Brasilero—with stops at the Casa de Susana Soca, the Zorrilla Museum, and the Mario Benedetti Foundation—the guests followed the trail of a country where literature is not only written, but lived.

“It has been a fascinating journey,” Tobón later said. “It gave me a much more complete understanding of what cultural life in Uruguay means.”

Aloisio described it as “a fundamental immersion,” adding: “I was moved by the way you care for your cultural memory so that current and future generations can enjoy and carry forward that legacy.”

In their meetings and during their time at the International Book Fair, both visitors were struck by the diversity and vitality of the contemporary scene. “I’m taking away a very positive impression of the sector; the effervescence that exists in Uruguay is not common in other countries,” said Tobón. “In illustration, the quality of the dialogue between image and text caught my attention; in fiction, I’m leaving with a long reading list,” he added.

Aloisio, who sees books as an accessible good, connected this vibrancy with a regional opportunity: “There is a cultural debt among our peoples. We need to look more at those who are close to us and exchange more; otherwise, the industry drags us toward the immediate and we continue reproducing ‘more of the same’.”

From a modernist tower to the soul of a literary city

The tour opened at the National Academy of Letters—the former home of poet Julio Herrera y Reissig, with its iconic Torre de los Panoramas—where academic Juan Justino welcomed the guests with the story of the Generation of 1900, pioneers of a bold, modern literary language. It was not a museum lecture, but a portrait of how Uruguay became a laboratory of modernity at the turn of the 20th century.

Justino reconstructed the atmosphere: a city that had ceased to be a village and become a metropolis; intellectual gatherings where Americanism was debated; and a group of writers who, alongside José Enrique Rodó and in dialogue with Rubén Darío, broke with established forms.

For an international visitor, the stop reveals one of the pillars of Uruguay’s literary prestige: a poetry that forged its own tone and conversed with the continent. It also points to a path still alive today: the tradition of “los raros”—that constellation of cult, unclassifiable, and visionary authors associated with Uruguay since the late 19th century. A lineage of singular voices: Felisberto Hernández, Juan Carlos Onetti, the Comte de Lautréamont, Marosa di Giorgio, Mario Levrero, among others.

“Seeing the house, imagining that space, and listening to such a masterful explanation of the author and his connections was very special,” Tobón said as he left.

Susana Soca: the woman who bridged two hemispheres

At the Casa de Susana Soca, now Ánima Espacio Cultural, hosts Déborah Rucanski and Sofía Casanova shared the remarkable story of the poet, editor, and patron born in 1906—a polyglot and natural bridge between Europe and the Americas.

During World War II, Soca founded the journal La Licorne in Paris and later continued with Entregas del Unicornio in Montevideo, publishing Jorge Luis Borges, Felisberto Hernández, Jules Supervielle, and Albert Camus.

Through these publications, she wove a literary network that linked Río de la Plata voices with major European figures. She edited Felisberto’s first French edition, corresponded with Camus and Supervielle—whom she translated and befriended—and cultivated ties with Borges and the writers of the Generation of 1900. Her editorial vision, alternating between authors “from here and from there,” was both cosmopolitan and deeply rooted in Uruguay. Her life ended abruptly in 1959, leaving behind a posthumous poetry collection and a biography that defines her as a rara avis.

For Tobón, the visit was eye-opening: “The Soca house was a revelation—understanding the significance of an editor who served as a bridge between Paris and Montevideo in the middle of the war.”

In the house of the ‘poet of the nation’

The next stop was the Zorrilla Museum, where guide Mariana Fernández welcomed the group with stories, paintings, and sculptures.

In the former summer home of Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, the narrative unfolds of a writer who gave epic voice to a young nation with Tabaré, the poem that recounts the encounter—and the wound—between Indigenous peoples and Spaniards. Tobón linked this with what he had seen earlier:

“Understanding how national literature was produced in relation to other Latin American literatures, but while standing in the places where it was written, gives it a completely different dimension.”

The guide also recalled that this house was the cradle of a family saga of artists: Zorrilla’s son, sculptor José Luis Zorrilla de San Martín, and his granddaughter, actress China Zorrilla, who embody the country’s cultural continuity.

Mario Benedetti: memory made methodical

The final stop was the Mario Benedetti Foundation, where Ana Montesdeoca welcomed the guests among manuscripts, photographs, the writer’s typewriter, and a meticulously curated library. She explained how the author of The Truce and Thanks for the Fire established the mandate to create an institution that would preserve his work, support new writers, and uphold his activism for human rights.

“I felt very clearly the respect with which Uruguay preserves the memory of its authors,” said Aloisio. “It’s a lesson I’m taking back to Brazil, along with a commitment to build bridges: to work with Uruguayan illustrators and writers and share this message with colleagues.”

Tobón echoed the sentiment: “These reverse missions are incredibly enriching. I leave with the great task of reading, reviewing texts, and finding bridges among our shared languages.”

A pause at Café Brasilero

One afternoon, the group gathered at Café Brasilero (1877), an Art Nouveau landmark and a sanctuary of the city’s literary heritage. Onetti wrote the first lines of El pozo here; Benedetti, Idea Vilariño, and Rodó were regulars; the menu pays tribute to Galeano with a coffee named after him.

That evocative mix is what Tobón highlighted: “The journey wasn’t limited to the professional. I had a closer, more intimate view of Uruguayan cultural life, which is welcoming and coherent.”

Aloisio turned the lesson into advice: “Don’t make the mistake I made—letting yourself be consumed by the machinery and not looking around. You have to look more at those who are close to you.”

A map for readers of the world

To a foreign visitor, Uruguay offers a unique literary equation: a diverse publishing ecosystem ranging from independent presses to consolidated houses; an institutional framework that preserves archives and writers’ homes; and a tradition of daring authorship with civic sensitivity.

This arc is embodied in names such as Zorrilla de San Martín, José Enrique Rodó, Juana de Ibarbourou, Horacio Quiroga, Julio Herrera y Reissig, Juan Carlos Onetti (Cervantes Prize), Mario Benedetti, Eduardo Galeano, Felisberto Hernández—and especially in a constellation of poets including Delmira Agustini, Idea Vilariño, Marosa di Giorgio, Circe Maia, Ida Vitale (Cervantes Prize).

Interwoven with these figures is the local idea of “los raros”—a devotion to the unclassifiable—that gives Uruguayan literature its recognizable mix: intensity, experimentation, oblique perspectives, and at the same time, a grounding in everyday life.

This journey showed two publishers how contemporary creation listens to its past—and how that past, preserved in museums, foundations, and academies, continues to shape editorial decisions today.

“Uruguay is a peculiar, even privileged place,” said Tobón.

Aloisio added with a smile: “I even feel a healthy envy—serenity, commitment, respect for the craft. If we manage to reproduce a little of that, the results will be very good.”